Editor’s note: We’re chronicling how tech is changing the way we eat and drink as we lead up to this fall’s Food Loves Tech. Our annual deep dive into appropriate food and ag technologies returns to Industry City on November 2–3, 2018—learn more and get your tickets here.

“What a beautiful glass cage,” a voice muses from headsets plugged into a virtual reality screen, which is depicting undulating hand-drawn illustrations of food. “I remember it being comfortable once.” One can’t help but recall at the sound of these words the night’s second course, which was served in a bell jar-shaped glass cloche that lifted to a plume of woodsmoke encircling rye noodles with pickled quail egg. And if you peek beyond the VR goggles, the next course is served in a wide, rimless white plate with a circular pattern piped in chrysanthemum puree, evoking an English hedge maze.

“In the end, being Asian American is a maze,” the narration concludes, reciting a poem meant to be heard, seen, felt and tasted.

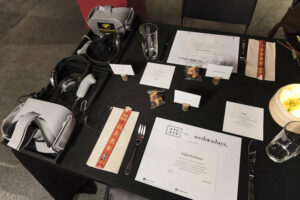

It’s about halfway through the “Asian in America” dinner by chef Jenny Dorsey of the popup series Wednesdays NYC and nonprofit Studio ATAO. If that sounds like a mental and sensory overload, well, at least it’s not your run-of-the-meal dining experience.

“We want to be the ultimate dinner party, where we’re not talking about the weather, or the subway or what Kim Kardashian did,” says Dorsey.

Dorsey has been hosting unique dinners with Wednesdays for the last four years. She says that the idea for the Asian in America dinner series evolved from dishes she had been experimenting with at previous events, as well as her own lived experience as an Asian American chef. Its first dinner was held last week at the Museum of Food and Drink in Brooklyn, and Dorsey plans to take it to other cities, like San Francisco, L.A. and Seattle, to start.

“I felt like I was asking my guests to be vulnerable, and I wasn’t being vulnerable enough,” says Dorsey.

For previous Wednesdays dinners, she explains, every guest has been required to complete a questionnaire in order to buy a ticket. The information they provided was used by the hosts as a jump start for discussions. So with the Asian in America dinners, she hopes to do what she can to foster those discussions first.

Each of the six courses in the Asian in America dinner highlights a loose theme about being an Asian American and how it relates to food. They come with titles like “Fancy Because It’s French,” which explores the double-standards of fine dining, or “Model Minority,” looking at that myth. And they’re accompanied by three cocktails that Dorsey’s husband, Matt, has expertly concocted to go with the theme. All told, the dinner will no doubt leave you asking questions and sharing ideas with your tablemates, the kind that obliterates the notion of polite dinner chatter.

We asked chef Jenny Dorsey more about what she hopes to accomplish with these dinners. To find out more and sign up for the next one, check it out here.

The following interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Edible Brooklyn: What do you think are the most important discussions around Asian Americans today?

Jenny Dorsey: One of the big things that I’ve been talking about with Asian media organizations is Crazy Rich Asians is the first movie with an all-Asian cast in 25 years. The representation of Asians in jobs is really low. Asians are “overrepresented” in elite colleges, but why is there no representation in media? And when it’s there, it’s always a stereotype. I flew Delta a week ago and [watched] the new safety video and there’s this one Asian lady and she has an accent … and it’s like, what is this? It’s 2018.

So representation is a big thing, and the issue of model minority is a weird double-edged sword. It’s like, be good and stay in your box so you’ll be accepted, but then you can’t move out. I think Trevor Noah said it best: When you’re a minority, you have to speak for everybody else. I get asked all the time to make other Asian food like Thai or Korean food, and it’s like, well, I’m not an expert on that. But I am actually an expert on French food. So there’s this idea that we need to be an expert when writing about French food, but anybody can write about Asian food. There’s a rigid hierarchy there and that’s a problem.

EB: Is there such a thing as “Asian American cuisine?”

JD: That’s like saying, “Is European cuisine a thing?” It happens when it’s easier to group everyone into the same thing. Even in saying that I’m Asian American, I’m East Asian, and my experiences aren’t the same as people from South Asia … so when I’m talking to other people I usually say I’m Chinese. But when you’re in a big group, it’s like, I’m Asian.

EB: What do you want people to take away from this dinner series?

JD: There’s a lot of unconscious bias about different types of Asian Americans, or in general about Asian Americans, being a minority. … The whole point of this dinner is that we’re all individuals. Everyone’s different, we’re just as multifaceted as people who come from Europe…. So basically, everyone deserves to be an individual.

EB: You were saying that you wanted to be more vulnerable. What do you want to share personally through this dinner?

JD: I do my best to not be really prescriptive, like, I don’t want to tell people to tell me what to do or vice versa. So I want it to be, like, this is my experience and I hope you have an open mind to hear what I say. … Maybe I can give you a personal account of what happened to me in order to say XYZ is a problem. Rather than saying something is racist. I find it’s better if I say, “This happened to me recently.”

I was doing an interview for a branded video shoot recently, and [the producers] wanted me to tell them about what I like to cook for the holidays, and after I talked to them, they were like, oh, well, we already had an Asian person in this shoot, can you tell us something else?

EB: Wait, what? I would have thought they would have the opposite reaction.

JD: Right? Like, literally, that’s what you wanted me to do. But it was more like they were asking me, can you give us the light version of this story rather than what actually happened to you.

Also, when I graduated from culinary school, all my friends got recommendations to work at places like Jean Georges, and I got three Asian restaurant recommendations. I never said anything to my career counselor to get that. That’s kind of offensive. So being able to talk about those experiences—sometimes in a humorous, sometimes serious way—that’s the point of the dinner.

EB: Why the VR?

JD: One of the things you hear a lot in the VR world is that it’s so isolationist, and one of the things I enjoy about VR is that it is so solitary and it feels very immersive. One thing I kept encountering at Wednesday dinners is that people often acquiesce to the group dynamic—say there’s one person at the table that really dominates the conversation. So with VR, you can really put them in a space that you have curated for them without any interference, and that is very important for the message that I want to have at this dinner.