As the sun sets on 2013, the Twittersphere has yielded a bumper crop of food-related resolutions.

It’s tough to improve upon Michael Pollan’s succinctly sage advice: “eat food, not too much, mostly plants”—but the NRDC’s resolution list includes Pollanesque practices, from “grow your own” to “cook at home.” And Good’s includes “host communal dinners” and “ferment something.” Come over and we’ll each raise a glass of kombucha to that.

Still, the best two such lists I’ve ever seen long pre-date hashtags and merit New Year’s re-reading.

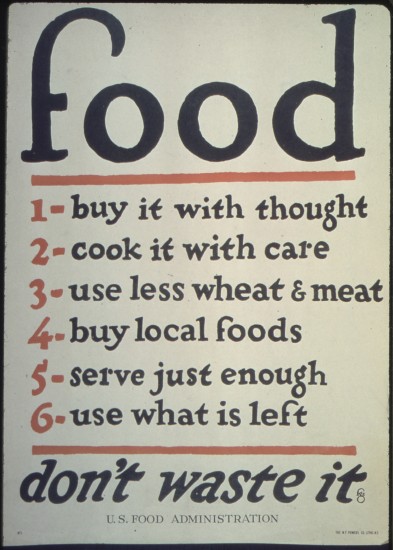

One is the image shown here, which remarkably was promoted by the “US Food Administration” back in 1917. Here’s hoping the USDA returns to its senses—and these messages—in 2014.

But my lifelong favorite list of food resolutions—and the underlying inspiration for every word of Edible Brooklyn—remains the 7-item specifically-for-urbanites list at the end of Wendell Berry’s 1989 essay, the Pleasures of Eating. And I quote:

How we eat determines, to a considerable extent, how the world is used. What can one do? Here is a list, probably not definitive:

1. Participate in food production to the extent that you can. If you have a yard or even just a porch box or a pot in a sunny window, grow something to eat in it. Make a little compost of your kitchen scraps and use it for fertilizer. Only by growing some food for yourself can you become acquainted with the beautiful energy cycle that revolves from soil to seed to flower to fruit to food to offal to decay, and around again. You will be fully responsible for any food that you grow for yourself, and you will know all about it. You will appreciate it fully, having known it all its life.

2. Prepare your own food. This means reviving in your own mind and life the arts of kitchen and household. This should enable you to eat more cheaply, and it will give you a measure of “quality control”: you will have some reliable knowledge of what has been added to the food you eat.

3. Learn the origins of the food you buy, and buy the food that is produced closest to your home. The idea that every locality should be, as much as possible, the source of its own food makes several kinds of sense. The locally produced food supply is the most secure, freshest, and the easiest for local consumers to know about and to influence.

4. Whenever possible, deal directly with a local farmer, gardener, or orchardist. All the reasons listed for the previous suggestion apply here. In addition, by such dealing you eliminate the whole pack of merchants, transporters, processors, packagers, and advertisers who thrive at the expense of both producers and consumers.

5. Learn, in self-defense, as much as you can of the economy and technology of industrial food production. What is added to the food that is not food, and what do you pay for those additions?

6. Learn what is involved in the best farming and gardening.

7. Learn as much as you can, by direct observation and experience if possible, of the life histories of the food species.

The last suggestion seems particularly important to me. Many people are now as much estranged from the lives of domestic plants and animals (except for flowers and dogs and cats) as they are from the lives of the wild ones. This is regrettable, for these domestic creatures are in diverse ways attractive; there is such pleasure in knowing them. And farming, animal husbandry, horticulture, and gardening, at their best, are complex and comely arts; there is much pleasure in knowing them, too.