“He smiled his huge grin, put the plate to his face, and licked it clean.”

—Marlon James, Black Leopard, Red Wolf

When Man Booker Prize–winning author Marlon James and I first spoke on the phone to plan our “Tables of Contents” dinner collaboration, I’m not sure he knew exactly what was coming. But when he and our other guests for the March event stepped from the sidewalk into the front dining room of Egg, met by the funk of bamboo and civet musk swirling from custom-made candles around the room, it began to settle in. Ahead on the bar, mismatched leather pouches slouched full of spiced nuts (anise-flavored pecans, curried peanuts, lavender almonds), enormous dates climbed out of black chamba bowls, and slices of cured pig lay beading sweat on slates.

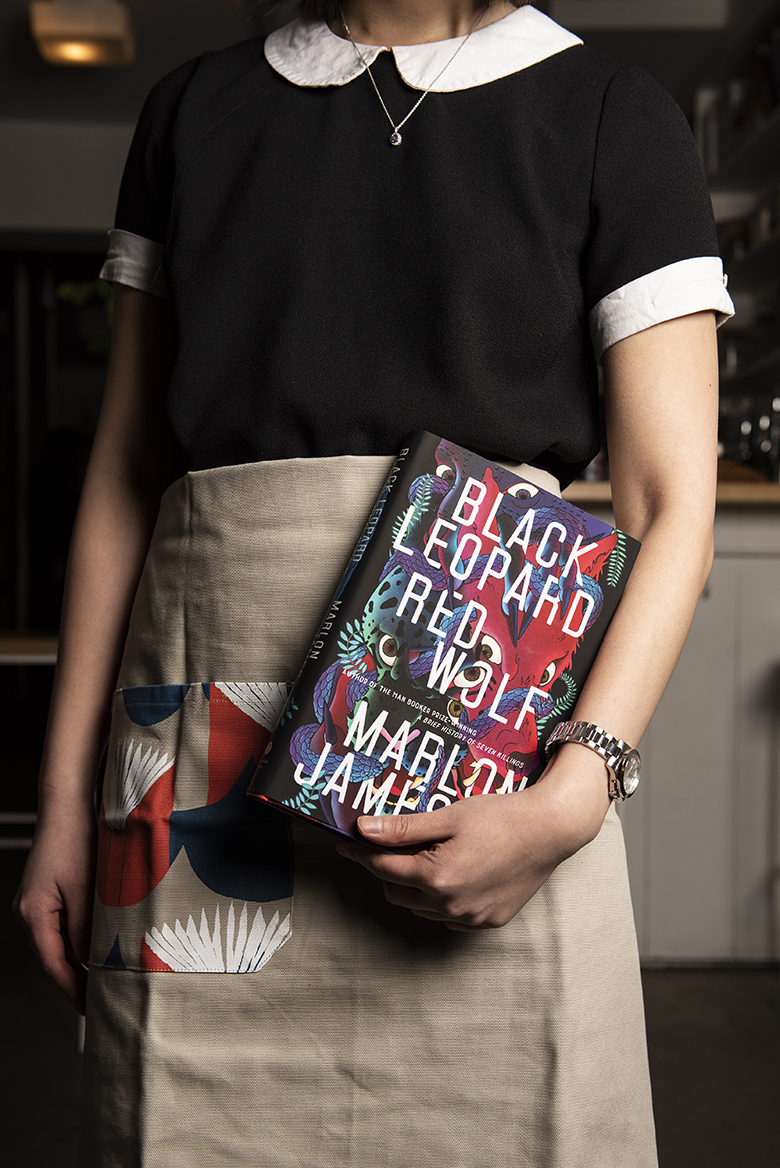

We feel this way sometimes as we enter a restaurant, the sense of being transported somewhere completely new. You could argue every restaurant is a sort of fictional experience, but the room that evening, at what was normally a breakfast-and-lunch restaurant that George Weld and I run in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, was exceptionally so: Every detail and bite of food had been drawn verbatim from Marlon’s acclaimed new novel, Black Leopard, Red Wolf, the first installment in his epic Dark Star Trilogy.

Seven years into our edible multidisciplinary experiment, this evening—a collaboration with publisher Riverhead Books, New York’s own Food Book Fair and Marlon himself—was probably the most ambitious Tables of Contents event yet. We began the series in 2012, when at the behest of our friends at Food Book Fair we prepared a meal inspired by Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises to close out their weekend-long celebration of food publications. It’s a book commonly associated with booze, but as we dug into the roast chicken and green beans, brook trout wrapped in ferns, and a closing bite of Pernod sorbet, we found there was a meal and more in there, too.

The thrill of engaging taste—the one sense untouched in the act of reading—and of the story literally entering the body was visceral. We were hooked, and in the years since have continued the project, cooking annual dinners and curating a monthly reading series that invites the best contemporary novelists, essayists and poets to a joint exploration of food and literature.

Leading up to the Black Leopard, Red Wolf dinner, I’d filled the blank back pages of a hardcover copy of the book with dozens of promising edible excerpts. Masuku beer (brewed from wild sugar plums), goat liver, the slice of a knife through melon, even an assassin’s body dissolving into wisps of ash. For the scenes that made it to the table that night, we sought out antelope steaks, millet, sorghum, and smoked African fish for a Thai-and-Norwegian-inspired soup, its scene dictating to us: she smelled like fish and lemongrass. We served shards of chicken skin atop a soft-cooked egg, blood sausage with milk and berries, ugali (cornmeal) porridge, loose like grits, topped with coins of spiced crocodile sausage, each dish aspiring to amplify the experience of the text and be lifted by the text in return.

About midway through the meal, a large white plate, spattered with a dark spray of blood sauce (reduced beet juice) and crowned with a loose mound of goat tartare was set before each guest with instructions: Eat the meat with your hands then lift and lick the plate, just as the protagonist, Leopard, licks a bloody plate in the scene printed on the accompanying bookmark. A pause, and then the walls broke down. They ate the meat, they licked the plates! Engaging in the animalistic, intimate act alongside previous strangers lent an air of euphoria to the room and sped the pace of the meal; the conversation swelled, the beer bottles clinked more firmly, the laughter peppered in faster. It catalyzed our transformation from unrelated individuals in a dining room to characters in the evening’s plot.

The meal ended with a return home, for Marlon at least, with a Jamaican goat curry inspired by the version he makes for friends. Served here in a cinematically American style were huge hunks of shoulder torn at the joints, in a Scotch bonnet sauce over soft white rice. It was too much, eight courses in, but then so is the book—sensual, physical, fantastical and intense.

In our closing discussion that evening, Marlon and I talked about the ways he deploys food in a story, the differences in our approaches to cooking and writing, and our literary (as opposed to culinary) allergies and aversions. I realized that, in our respective fields, we’re really trying to do the same things: create a stimulating experience and provide people with something they need. Which makes sense. Language and food, two of the most basic elements of our lives, both reflect our histories and create our cultures, on the plate and on the page. If we are what we eat, it seems that a steady diet of considerate food, art and ideas should help make us the kinds of characters we aspire to be. I guess Tables of Contents is asking, why not consume them together?