On a humid night in July, Stephanie Shih sat down in her studio and folded 30 identical clay dumplings by hand. The next day, she folded 30 more and the day after, 30 more.

What prompted the 32-year-old ceramic artist to methodically shape nearly a hundred replicas of a Chinese dish she grew up eating is still unclear to her. The plump, smooth porcelain dumplings were unlike anything she had created before yet the rhythm of rolling, folding and pinching the thin discs of clay into small dumplings felt deeply meditative and reminded her of working with the actual dough.

“It was this muscle memory of folding them with all my āyís [aunties] around the table where everyone is teasing each other, like, ‘Yours are ugly. No yours are ugly,’” grins Shih, seated in the quiet basement of Gasworks NYC, a clay studio in South Slope where she hand-builds ceramics. She’s currently working on an upcoming exhibit (location TBD) titled ORIENTAL GROCERY that examines first-generation nostalgia through replicas of Asian-American pantry and kitchen staples.

The concept for the project quickly evolved after she first posted photos of the dumplings on Instagram and was overwhelmed by enthusiastic support from fellow Asian-Americans who were from culturally different backgrounds living in different parts of the U.S. yet shared a deep nostalgia for the same things that shaped her own experiences growing up as a first-generation Chinese-Taiwanese kid from Central Jersey.

The response from white people, however, often treated the dumplings like a joke. “They didn’t see it as a sculpture, they saw it as some kind of novelty,” says Shih of Internet strangers and friends alike who impulsively asked when she was going to make soy sauce and fortune cookies, and suggested that she sell the dumplings in egg roll wrappers or Chinese takeout containers. “They’re not egg rolls and it’s not rice,” Shih says flatly. “It’s not like I started this project to connect with my dead āyís or whatever, but those interactions made me start thinking more deeply about it.”

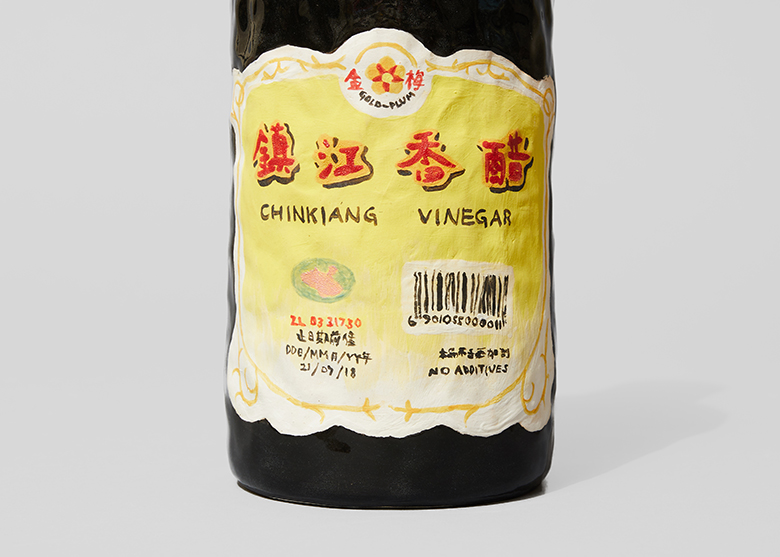

Three weeks later, she launched a site to sell the dumplings, including a limited series of lucky gold-lustered “dumps” (as she affectionately calls them) but not before releasing the ceramicist equivalent of a mic drop: a photo of an intricately hand-painted bottle of Gold Plum Chinkiang vinegar, its label written in English and Chinese. The post was accompanied by a caption that read, “the real ones know.”

The rice-based black vinegar is a central ingredient for the sauce traditionally used to dip dumplings in, something Shih knew few non-Asians could relate to, whereas all Asians would be able to rally around its cultural significance. Likes, comments and the dialogue that followed motivated her to create more space for Asian-Americans to reconnect with their childhood memories and cultural identity through food they all grew up eating. After making a 50-pound bag of Kokuho rice, its top rolled down and its bottom lumpy from her fingerprints, Shih jokes that she didn’t know rice came in smaller quantities until she was 20-years-old. A small red-tipped bottle of Yakult, Japanese fermented milk, reminds everyone that kids like her were drinking probiotics long before it was trendy.

Food carries meaning for everyone but maybe especially people who have only known life in the diaspora, whose identities are tied to a figurative homeland that “exists only in the memories and experiences that this set of people have had,” Shih explains. Asia-America isn’t a location on a map, she continues, but is “a collective of people who happen to live here.”

Memory is fleeting and branded objects change over time which means Shih has to research details like the brand of oyster sauce from Hong Kong everyone remembers using, or the color of the lid on the bottle of Vietnamese garlic chili sauce that was always in her parents’ refrigerator. Social media polls, phone calls with her mom, and digging around on the Internet for images of labels as old as she is have brought answers to looming questions. But no matter how explicitly her polls hail people of Asian backgrounds, “white people always respond,” she laughs, shaking her head.

Shih was raised with one younger brother by Chinese-Taiwanese parents whose love of home cooking laid the foundation of her fascination with food. At two years old, she insisted on sitting atop the kitchen counter next to her mother who was busy preparing meals and often wielded a large Chinese cleaver. By middle school, she taught herself how to cook, usually baking and never her parents’ cuisine. Attending a racially-mixed school with a large Asian-American population didn’t shield her from internalizing the notion that being Chinese meant “you can’t be cool. You have to be white to be cool,” she remembers.

It wasn’t until college where she studied hospitality management and media, surrounded by mostly white friends and classmates, that she began to see Asian-Americanness as an essential part of her identity rather than something to downplay or assimilate to white norms.

For the next eight years, Shih navigated front- and back-of-house positions in restaurants and catering businesses in Boston and New York City before settling into design work. Over the last three years, she has nurtured her childhood love of art, something that was “out of the question” for her to pursue in school, into a growing side career as a ceramicist. Ceramics is a form that has a long tradition in Asia, she tells me, but is commonly practiced today in places like Brooklyn by predominantly white people who learn to shape Korean moon jars, Peruvian water jugs and Japanese sake sets—relics of someone else’s culture—for their own skill development and personal profit. The more she considers what it means for non-Asian people to make art (or food for that matter) from a history and culture they have no connection to, the more she wants to make something explicitly centered around her own personal history as an Asian-American.

Shih isn’t shy about calling out tactless assumptions of white people on social media, and it’s led to a noticeable shift in conversations about her replicas that include more respect and less presumptions. But this project isn’t an educational platform for people who equate Chinese cuisine with soy sauce and fortune cookies. Each piece offers an opportunity to share something that goes deeper than the food or the art and to connect with other Asian-Americans around food, like sweet Chinese haw flakes and Italian Ferrero Rocher, that symbolize their particular experiences and memories.

“I think it feels important to me to create space because we don’t have a shared physical place. We have to create dialogue and that becomes the space that we have,” says Shih, hopeful that other first-generation kids balancing dual identities will see her work and recognize themselves in it. “This is ours and it’s just for us.”