Editor’s note: We kicked off our first annual Food Loves Tech event last summer in Chelsea—here’s a recap. We’re bringing a taste of the food and farming future back this year but just across the East River at Industry City. Leading up to the event, this story is part of an ongoing series about technology’s effects on our food supply.

On a bright Saturday morning in April, a band of home cooks, health enthusiasts, artists and amateur biologists stagger into a seventh-floor co-working space on Flatbush Avenue in Fort Greene. Armed with notebooks and coffees, the group is ready to learn the fermentation process used to prepare kefir and yogurt.

It might seem like a fairly common (if not somewhat cliché) Brooklyn scene, but this class goes beyond an intro home cooking course. It’s held in a fully equipped research lab that’s got a casual, scrappy feel. The class (led by Cheryl Paswater of Contraband Ferments) also involves discussions about the bacteria used in fermentation and how they affect the gut microbiome, which is appropriate for this group since, more than an office, test kitchen or studio, Genspace is the country’s first nonprofit biotechnology lab dedicated to promoting science literacy and innovation at the community level.

By offering group classes and public access to high-tech equipment traditionally found in university or pharmaceutical labs, Genspace allows community members to experience science through playful experiments.

“The idea is that no matter what your interest or level of experience with science, anyone can engage with biotechnology,” says Nica Rabinowitz, a community manager, textile artist and educator at Genspace.

Three of the founders first met through an online DIY biology group during the mid-nought rise of the so-called maker movement. They started hanging out in founder Daniel Grushkin’s Park Slope apartment where, for fun, they tried to extract DNA from crushed strawberries and genetically engineer E. coli. After each experiment, though, the group had to tear down their setup and decontaminate the apartment. They decided that the ideal way to continue would be with a dedicated space, and in 2010, they opened Genspace for a growing community of biology hobbyists.

The lab still maintains a distinct DIY feel seven years later. Most of its equipment—including centrifuges, electrophoresis machines, incubators, microscopes and glassware—is donated. The experiment area is enclosed using old glass doors and wire screens, and almost like a commissary kitchen, the scientific gear sits on stainless-steel restaurant shelves. The community and lab managers ensure it maintains basic government standards, Rabinowitz says.

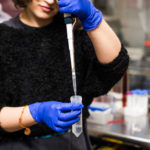

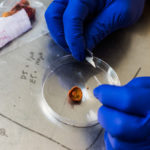

While the kefir class takes place near the equally hodgepodge kitchen, Genspace member Peter Russell tinkers around the lab, chopping crimson-colored waxcap mushrooms into tiny little pieces. He scoops the crumbs off a Petri dish into plastic tubes and proceeds to use a soapy liquid to break down the mushroom cells and extract their DNA. As a former botanist, he’s interested in identifying which genes help the mushrooms grow in various types of soils. “I come all the way from Texas whenever I get a chance because Genspace is the only lab where I have access to the equipment needed to do this,” he says.

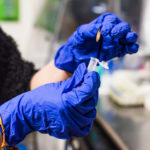

Even those who haven’t cracked open a biology textbook since high school can learn the advanced techniques through an assortment of classes, though. “You can come in, have no previous lab experience, learn how to pipette and in the same day get into more advanced stuff like how to sequence your own DNA or work with bacteria,” says Rabinowitz. “That’s the whole magic of Genspace.”

One upcoming class, for example, focuses on teaching individuals how to isolate DNA and understand what it reveals about their food. Under the supervision of a professional scientist, learners will get to remove and read the wheat DNA in their bagels using some of the same techniques Russell employs.

In another class with bioartist Stefani Bardin, students will discuss how to design food for the future. They’ll learn about biotechnology that helps maximize food yields and make agricultural practices more sustainable.

On weeknights, members will also have the opportunity to to learn gene-editing à la CRISPR, a revolutionary technology that allows scientists to precisely modify DNA inside cells. Lab manager Will Shindel plans to show students how to use CRISPR to delete a gene in brewers’ yeast and make it glow red. He’s also set aside a group of potted tomato plants in the lab, hoping to use CRISPR to eventually engineer a spicy tomato.

The larger goal isn’t to commercialize the projects developed at Genspace, though. The lab focuses more on consumer empowerment and creativity. “It’s about the hands-on experience and the collaboration and understanding biology in your own way,” says Shindel.

Participants can dabble in any biotechnology project they want as long as it is approved by Genspace’s scientific review board. The lab takes bioethics and safety very seriously: Everything is biosafety level 1 certified, which means that members don’t work with any pathogenic materials that may make people sick. They don’t do any experiments on animals, and if students modify any organisms as part of a class or project, they generally aren’t allowed to take those home, Shindel explains.

But making the tools and biotechnology accessible to artists, biologists and home cooks has great implications: It demystifies a complicated science and opens up discussions about how these tools can and should be used, Shindel says. “Once people get to experience biotechnology hands-on and see what its quirks are, they have a more well-rounded understanding of what it can and can’t do and how it applies to their lives.”