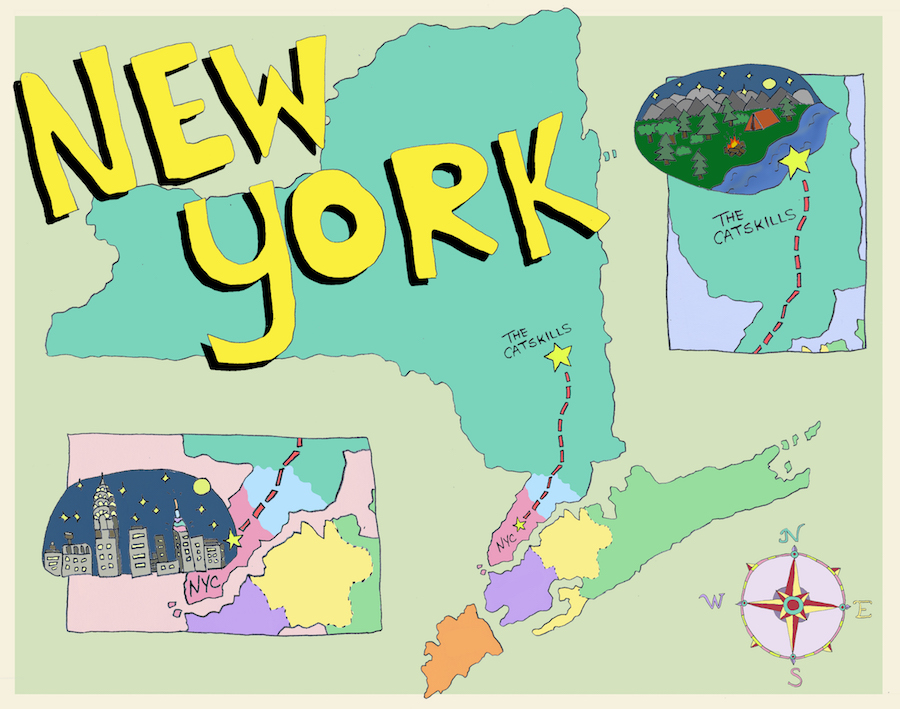

I went to the Catskills to live simply, more or less. To try to line up the life I had with the life I wanted. My head was full of ideas from books, ideas from Eliot Coleman and Wendell Berry in particular. From Coleman I got the idea that the land I sought for a small farm would slope gently to the south or southeast, that it would be protected from the prevailing winds by a low rise or hedgerow, that it would have ample water and variable shade. From Berry, I had the thought that the place we lived would be a place we learned to love, a place we got to know every stick and twist in, set in a community we would help build up with our industry and commerce and affection.

I envisioned a farm that not only provided my restaurant, Egg, with its produce, but also helped create an exchange between the rural communities outside the city and the city where we mostly lived.

In 2007, we found just such a place on the northern edge of the Catskills. The land was perfectly situated, with a livable house and fairly stable barns on a small piece of promising-looking land. It was on the edge of an old town, Oak Hill, that retained some hints of its glory days, when small-time mill owners were able to build small but stately houses on Main Street—though now it was mostly quiet, flickering with life but not enough work to keep everyone well-employed.

We bought the place and right away started pulling up grass to plant vegetables, turning over soil with spades and covering plots with the wall-to-wall carpet we pulled out of the house, hoping by smothering the upturned sod we’d generate a rich topsoil that would yield to the tiller we meant to buy and produce bushels of beans and tomatoes, crates full of pumpkins and melons.

The next spring, tiller in hand and books at the ready, we started in earnest. We’d ordered about half the seed catalog to plant, and plant we did—but we also learned a maxim about the Catskills that neither Berry nor Coleman had prepared us for: You know you’re in the Catskills, the saying goes, when you get two stones for every dirt. Our land was as rocky as a scree field, barely covered by a layer of topsoil. Seeing it, I finally understood the bewildered looks I’d gotten at farm supply stores when I went to ask for eight-foot wire fence to keep the deer out of our vegetables. We had to have that ordered special. Most people had enough sense not to try to grow vegetables in this soil. The deer were the least of our problems.

And as we learned our way around the soil and the town we’d bought into and the mountains we farmed in the shadows of, I learned something else about the Catskills: I was not the first person to come rolling up from the city with a head full of big ideas only to find that these hills had their own lessons to teach. I’m not sure any landscape in America has had more fantasies projected on it than the Catskills. In the 17th century, European settlers dreamed of digging in and finding gold among those hills; a later generation re-created a feudal fantasyland that allowed them to live like Old World lords well into the 1800s, long after the Revolution had put most other colonial fantasies to heel.

The first recognizably American movement in art—the Hudson River School—took the mountains as its inspiration, painting the falls and sunsets of the Catskills with hallucinatory intensity. Industrialization and modernity brought waves of people up from the city pursuing health, splendor, fresh air and, once the resorts of the Borscht Belt had hit their peak in the mid 1900s, a good show. Until we ended up at Woodstock, the biggest show of all.

Fantasies on a smaller scale were taking shape and dying out through all those years, too. In the late 1960s, when he was still a young chef working for Howard Johnson’s in the city, Jacques Pepin moved to the Catskills because it reminded him of the French mountain towns he’d grown up in. The area around Hunter and Tannersville became an “enclave for expatriate French chefs,” wrote Pepin. “Life was good in Hunter. Trout, frogs, mushrooms and garden produce made Hunter a paradise for anyone who was passionate about food.”

In the 1990s, the artists McDermott and McGough came up from the city to Oak Hill, and found there, among the well-preserved old buildings in town, the stage for a massive performance of living art, an experiment in “creating life in another era.” They moved in and lived as early 19th-century swells, getting around by horse and buggy and Model T, eschewing electricity and plumbing and other modern conveniences. For them the Catskills provided the opportunity of time travel, transporting them to an alternate universe to the East Village art world of Basquiat, Haring and Schnabel where they’d gotten their start.

But because these are fantasies, usually launched by city folk, they fade and disappear. And when the fantasies recede, they leave almost nothing behind. There are no signs of Pepin’s tenure in Hunter, no memory of McDermott & McGough in Oak Hill. Monuments to a previous generation of dreamers fade almost as fast as they grew up.

Even the Catskill Mountain House, a 19th-century hotel so grand that it was visited by three presidents, was allowed in the 20th century to decay and collapse, and today there’s no almost no sign of its existence—no local preservation association came along to shore it up and keep it vital, no family legacy depended on its continuation. Railroads that used to carry tourists up from the city for fresh air and fishing simply vanished. The names of the great land barons who controlled the region from the early 1700s through the middle of the 19th century—Hardenburgh, Livingston—are little known. Few people even know where Woodstock—arguably the most significant event in the Catskills within living memory—took place (not in Woodstock).

And so, for a place with such a storied place in American history, the Catskills seem to have a remarkably scant native culture—if they have any at all. When we moved up, I expected I’d do what I’d done every time my family moved to a new place down south: find the people who’d lived on the land for generations, the old families on whose legacies the community was built, and learn from them how the place worked. But with very few exceptions, all the people I met in the Catskills were other refugees from the city—they’d just moved up a decade or two earlier, from Bensonhurst or Gravesend or the Bronx. Many of them still depended on the city for work, commuting back and forth regularly. For them success had meant escaping the grime and congestion for a simpler, slower life, even if it was compromised by the necessity of going back into the maw of Manhattan twice a month to make it work.

In a way the Catskills resemble New York City, the place that they serve as a foil to and escape from. As they do in the city, people alternately flock to and flee from the area, and when they go their memory is almost instantly swallowed up by the continuing movement of time. The identity of the Catskills churns, evaporates, condenses, changes with the seasons. It’s as though the sedimentation that created the Catskills geologically continues culturally, covering over each successive generation with something new, sealing off the past.

So the old leather-tanning communities of high mountains can become ski towns that give expatriate French chefs the comforts of their alpine country homes; so the old fly fishing town of Phoenicia can be reborn as a kind of fancy Brooklyn outpost with a boutique hotel and good restaurants and absorb the fantasies of visitors from Bushwick and Fort Greene who have no interest in casting for trout.

It makes the Catskills an odd place to think about putting down roots. The lure of the nearby city may make it more unlikely than usual that successive generations will stay on the farm or running the family store, even if that farm may thrive for a generation by its access to the city’s Greenmarkets, or that store succeed by serving a generation of tourists. For many, it’s tough to make a living in the Catskills. The towns are small and unstable. The land is beautiful but uncharitable. What seems to flourish here are groups of people cultivating a particular way of life: communes and intentional communities like the Bruderhofs or the Twelve Tribes. And it may be that those are what the Catskills do best: provide ground for experimenting with new and better lives.

Perhaps the best book about the Catskills is a young adult adventure novel—My Side of the Mountain, by Jean Craighead George. The book itself, when it was published in the 1950s, was the germination of a million dreams of escaping to the woods, living off of nuts and berries, befriending wild animals and escaping the wild humanity of the city. The main character, a boy, has run away from Manhattan to make himself at home in the mountains near Delhi, on the west side of the Catskills.

He hitches a ride into the woods with a local, then abruptly asks to be let out as they pass through a stretch of forest. Is this where you live? The driver asks.

No, says the boy. “I am running away from home, and this is just the kind of forest I have always dreamed I would run to. I think I’ll camp here tonight.”

Illustrations by Gabrielle Muller.