The supermarket — that shining symbol of modern convenience and endless abundance — is trending toward extinction. The assaults are coming fast, and from all sides. Gas stations and discount outlets are hawking food and swiping market share. Shoppers craving seasonal produce and prepared meals are happier with options at farmers markets and specialty grocers. Just 20 years ago, supermarkets collected three out of four grocery shopping dollars. That share is now well below half and approaching one quarter. American grocers plan to shutter nearly 600 stores between now and 2018.

At the same time, consumers are hungrily sampling a bumper crop of eager, nimble upstarts like Farmigo and Good Eggs and Instacart, the last newly allied to deliver Whole Foods Market items in just a few hours. Then, seemingly out of nowhere e-commerce titans barged into the gastronomic game, including AmazonFresh (now operating in Seattle, San Francisco and Brooklyn), GoogleExpress’s food and drink offerings and Overstock’s farmers market. How quickly the tables can turn. Target and Wal-Mart, which were considered successful entrants into food selling a few years ago, are already losing share to online ordering, according to a report from Goldman Sachs.

“Supermarkets should be afraid of being the next Blockbuster,” Danielle Gould, founder of the food-innovation tracking site Food+Tech Connect, recently told Edible San Francisco. “Shopping online for food may seem niche now but, five years ago, so did getting movies online.”

In fact, while 18 percent of Americans say they have bought groceries online, total sales are just 2 to 3 percent of our nation’s grocery budget. Still, they are growing by 20 to 50 percent per year in leading markets, and on target to hit $100 billion by 2018 according to Boston Consulting Group. Young families, Millennials and higher-income shoppers are much more likely to buy their groceries online, especially as it becomes easier. Foodily and Fresh Direct collaborated on a web plugin that will convert any online recipe into a shopping cart of those ingredients. Publix rolled out deli ordering, and Peapod launched click and collect, in which shoppers just drive to store and pick up food already bagged by employees. Kroger, no trendsetter in this category, has already seen millions of customers download its mobile shopping app, including 400 million e-coupons used.

And these trends aren’t limited to America and Europe. (It’s a global food system, after all.) In India, online food sellers “Bigbasket.com and Localbanya.com turn in profits while supermarkets are struggling,” according to Reuters. It’s been more than a year since Time declared, “The Grocery Store May Be on Its Death Bed.”

What’s a brick and mortar supermarket to do? Think ahead. As in, light years ahead. At least that’s what Mike Lee thinks they should be doing. He and his team at the Fort Greene food design and innovation agency Studio Industries, whose bread and butter is helping tease out beautiful, innovative, tech-driven solutions to serious food problems, have opened The Future Market, an ongoing project that exists as an online destination featuring futuristic grocery products and, in early 2015, a pop-up destination so that consumers can truly experience the grocery store of 2065. We recently spoke to Lee about the project, why he takes dates to supermarkets and why grocers who want to survive should be beating a path to his door.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Edible Manhattan: What was the inspiration for The Future Market? Was it for a particular client or something your team created to provoke thinking in terms of food marketing in general?

Mike Lee: It’s a project that no client was asking us for. We wanted to do it because we think it’s the sort of thing that food industry should be thinking about.

Think of it as your neighborhood grocery store. Just the one that exists in the year 2065. It was brought to life by a collective of food innovators, designers, economists, scientists, marketers and entrepreneurs. Our goal is to raise the bar for innovation today by thinking more ambitiously about the food products of tomorrow.

EM: So the food industry isn’t thinking about innovation?

ML: The word “innovation” has completely different meanings depending where you are. What it means in food world is not same as tech world. As we spoke to food and drink brands and supermarkets and others about how they innovate, we asked, “Is this it?” We wanted more. We wanted to believe that food could innovate as fast as other industries. Look at Tesla and Elon Musk and he’s so far ahead of transport industry. It’s amazing. So we wanted to ask why there isn’t something like that in food.

EM: Is the Future Market a bit like a concept car for the food industry?

ML: Exactly. Concept cars have been a normal thing at auto shows for decades. It’s embraced to see something not practical today. But people say maybe we can do something this year. The Future Market is really based on what a grocery store and its products could look like in 2065.

We exist to shake up today’s food industry, that too often innovates one foot at a time. Instead, we want to aim 50 feet ahead. From concept cars to package-delivering drones, let’s take a cue from the tech and automotive industries. Big thinking energizes innovation, and we want to bring this to the food world.

EM: The FutureMarket sounds a bit like the 10-year, 50-year, 100-year predictions that folks like Ray Kurzweil (now chief engineer at Google) and Stephen Hawking have been famous for making.

ML: I’ve been reading a ton of Kurzweil! We took a lot of cues from science fiction: in 2001: A Space Odyssey, he’s eating his breakfast and using a tablet talking to someone. Would we have gotten to iPad and tablet without it? I like to think that some child was watching that movie and said, “I want to get there.”

EM: And why the half-century time horizon?

ML: It is sufficiently abstract. It’s a time frame where people could put their guard down and dream a little bit about what an amazing outcome, or a scary outcome, it could be and then reverse engineer what you want to do based on that. I don’t want to start with a two-year vision — I want to start with 50-year vision and come back to two-year vision.

EM: What do you mean by reverse engineer in this case?

ML: We’re really going to pay attention to the steps. That this happened in 50 years, because this happened in 40, and this happened in 30. Look at things happening on a smaller scale today and what happens if mainstream 50 years from now.

We want to do this in a very solutions-based sort of way. I want to be able to say to any potential corporate partner: “What do you think the cheese industry is going to look like in 50 years?” and what can we do to prototype it? What can you do in two years to get to 50 years? I want to be sensational and substantive. I don’t want it to just be a sort of art project. I want to be able to change things.

EM: So, what’s an example of this sort of rapid-prototyping and envelope-pushing innovation at work?

ML: Think of the meatless hamburger. In 2011 scientists were growing cow stem cells in petri dishes and estimating it would cost $325,000 to grow a hamburger that way. Now we’ve got Impossible Food’s making a plant-based patty that looks, feels, smells and tastes closer to a hamburger and it costs just $20. That’s the sort of change we’re talking about in food.

It’s a little bit like the first video games. The first video game in 1979 was extremely laughable, too, but you accelerate that technology and look where we are today: Minecraft, Occulus Rift, platforms like Twine in which anyone can build a video game that’s infinitely more realistic than Asteroid’s ever was. So we applied the same type of reasoning to the grocery store.

EM: Is any supermarket innovating in this way?

ML: There are examples here and there. Whole Foods Market did a bang-up job with its concept store [with touch screens at the ends of aisles that provided nutritional data, grower stories and recipe ideas], and we were inspired by it. But this is not the rate of change of when Napster disrupted the music biz.

EM: Your mock-ups and description seem to assume the market of the future is brick and mortar: a physical space, as opposed to a Fresh Direct or some other distributed solution. Do you feel both will still exist, like my hopeful assumption that there will still be print magazines even as digital media grabs more readership?

ML: We definitely believe that the brick and mortar solution will coexist with the more virtual, distributed solution in the future. In fact, The Future Market will have a strong virtual representation on the web in addition to the physical store. Overall, we think the brick and mortar will become much more dynamic, customizable and flexible, while the distributed solution will become more efficient and quick than it is today. And regardless of what technology will enable us to supply people in either domain, we want to explore what society would value having still in a physical location, versus what we’re OK choosing online and having brought to us at another time. For instance, we’ve observed that most people like to feel and choose the individual apples they buy but could care less to touch the box of baking soda they need and prefer it delivered to their door. Depending on how well this dynamic holds true 50 years from now will certainly influence the balance of physical and virtual markets.

EM: The store looks sufficiently Jetsons-esque with sleek lines, pure white aisles and edible surfaces popping out of everywhere. It’s chock-full of certain store layout innovations we’re starting to see here and there but bumped up to the next level of shopping integration.

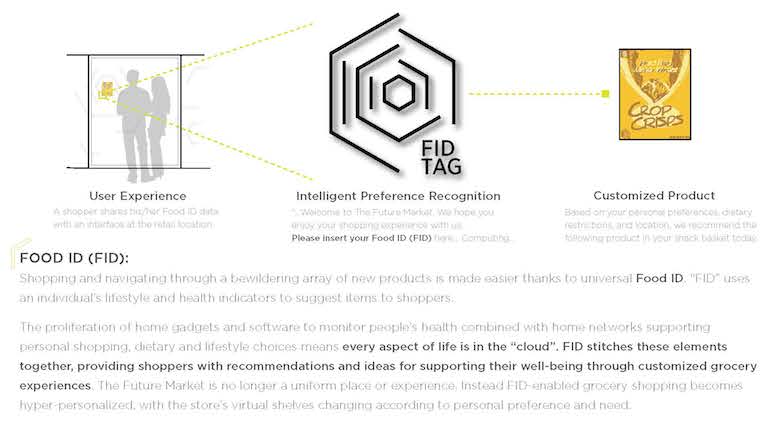

ML: If you stroll around the space, you see Automated Fulfillment Lanes, where shoppers find and select items on digitally interactive shelves and receive them on the way out. There are Digitally Interactive Product Shelves that are touch activated and can tell a far richer story about the products than antiquated, physical shelving. [There’s also] a Food ID Platform where shoppers can scan their personal Food ID data that contains information on nutrition needs, allergies and tastes, all updated in real time. Finally, here are two types of food production integrated into the store: Hyper-Efficient On-Site Farming and Custom Food Production depending on local shopper demand.

EM: I was most fascinated by what’s on the shelves. Your signature product Crop Crisps works from the assumption that Big Ag has finally embraced diversity and crop rotation.

ML: So far we have only released the one product: Crop Crisps. You might think of them as seasonal Wheat Thins. They are a type of snack cracker, and they come in four different flavors or varieties, each corresponding to a different crop in a multi-year, soil-boosting crop rotation. The four flavors are hard red winter wheat, lentil, white winter wheat, and favas/garbanzo.

EM: That reminds me of Dan Barber’s rotation risotto and some of the other future dishes he considered in The Third Plate. Considerably more appetizing than astronaut ice cream. Anything else we can expect on the shelf next to Crop Crisps?

ML: We didn’t prototype anything beyond Crop Crisps yet, but we have over 12 additional ideas we’re working on right now. In the 60 days we had from our initial design sprint to the expo [Northside Festival’s Innovation Expo], we wanted to focus on one idea that we thought would tell a story but have mass appeal: that was Crop Crisps. There’s much more to come though.

Really we’re a retailer of ideas, and not just our own. Food is universal, and tomorrow’s looming environmental, economic and societal issues stand to affect us all. That’s why the Future Market is open-source and industry-agnostic.

EM: I am fascinated by the fact that you’re looking not just at how market design will change, but how our culture around food will evolve. We’re clearly seeing technology accelerating with the adoption of drones for farming, the proliferation of food-tech start-ups, the ubiquity of assistance apps like Delectable and Resy.

ML: I’ve got to stress also the two streams to explore: the acceleration of technology and the acceleration of culture. This grocery store is not for us, it’s for our grandchildren.

We explored the details of life in 2065 and how societies are changing, too. Our grandparents right now scoff at stuff that kids today think is really normal.

EM: Like the openness of more and more people to buying food online — a foreign concept just a few years ago. Or the notion of “your aisle” that FreshDirect is developing with RazorFish: the idea that no one wants to stroll down 20 different aisles to find their food, but simply wants to go straight to the one aisle customized for them.

ML: Yes. Our grandkids will expect everything to be hyper-personalized. The idea of one size fits all will be antiquated. Which is very hard for a grocery store where a lot is one size fits all. Can’t make everything on the fly, but there is going to be more personalization. People will demand a lot more, being me-centric. Consider the Custom Food Production that we prototyped, which involves grocery stores producing customized food to order, efficiently, nutritiously and deliciously. This is the end of “one-size-fits-all” products.

We assume everyone in 2065 will carry their personalized Food ID around everywhere they go, and grocers and restaurants can read this universal data standard and create food tailored to each person’s Food ID. The proliferation of home gadgets and software to monitor people’s health combined with home networks supporting personal shopping, dietary and lifestyle choices means every aspect of life is in the “cloud.” Food ID stitches these elements together, providing shoppers with recommendations and ideas for supporting their well-being through customized grocery

EM: Right, personalization will be a bigger part of our food culture, like Zipongo (working with Google to help corporate employees make better food choices) or a highly person-specific Good Eggs box. Any other cultural shifts that you are imagining? If you believe Kurzweil’s predictions by 2065, we’ll be well on our way to being part cyborg, depending on machines/AI for much of daily life, and maybe even not having bodies sustained on food.

ML: One of the many cultural shifts that we think will strongly define our society in 50 years is the return to a culture of makers, especially for food. We’re already seeing this today with the rise of so many amazing small, artisanal food brands, and a renewed mainstream interest in home cooking. So, magnify what’s happening today to an extreme level and what you get is a society where individuals and groups have virtually no barrier to creating something that they think should exist in the world. Look at how digital tools already enable anyone in the world to create a website and express themselves on the Internet, which chips away at the power of mainstream media. Truly democratized production of physical goods — food included — are just a few decades behind digital goods, in terms of what the average person can create. Tools like 3-D printing, urban farming and even access to incubator kitchens are empowering us as a society to have more media to express our individuality and redefine ourselves as craftsmen. By becoming a culture of makers again, the world benefits because we’ll have much better choices and happier, more fulfilled people.

EM: How was the Future Market received at the Northside Expo? The expo had a bit of a World’s Fair feel to it. Were you happy with the reaction of those who stopped in?

ML: It exceeded our expectations. We got a lot of funny looks at first. Once people got reeled in and we could tell a story a bit they got very excited. The Tomorrowland of Disney World can be very compelling and enticing. We’re all of that, but for the grocery store.

EM: Even if you’re trying to deconstruct and re-imagine the supermarket, you seem to be obsessed with it.

ML: We love grocery stores. In high school, I went on a date to a grocery store. It’s just invigorating. I love walking up and down the aisles. If you love art, you’re going to love museums. If you love food, you need to love grocery stores, not just restaurants.

EM: You also created a conceptual newspaper to give a sense of what the zeitgeist of the future would be. The headlines include “Big Food Embraces Crop Rotation,” “Deep Volley, IBM Tennis Robot, Defeats Federer III,” and weekend weather that is mostly extreme flooding and severe storms. But there’s a fair bit of optimism in your headlines, including a story about EatRx, a hotly anticipated app feature that “identifies foods that provide health benefits previously received from traditional pharmaceuticals.”

ML: We strive for our year 2065 food ideas to be sensational yet substantive. Each of our concepts stems from a logical progression of events and trends. Our process starts by examining details of life from today, including key work, life, community and family structures, and then pushing these out decade by decade until we find ourselves in the year 2065.

EM: Do you have to start with optimistic assumptions so folks don’t get depressed? You seem to think that good food will be more affordable, that food companies will be mission-based with goals to further sustainability and healthy eating. I’m already beginning to sense a type of pushback from certain sectors of the food community, who see start-ups like Soylent and Monsanto buying Climate Corporation seemingly moving us farther from our food producers, farther from the soil and into creepy territory.

ML: I don’t think all companies need to be mission based in the future. There’s so many levers in innovation that we can explore. There is the state of the edible food itself, the Hampton Creeks of the world that care about the packaging, carbon footprint and traceability.

It’s going to have just as much of a mix of positive and negative as we do today. There will be some products that come from sustainable places and some that don’t. Our in-going assumption is that this distribution is going to be roughly the same. We’ve only released the tip of the iceberg. Ultimately this store is going to be 70 percent utopian and 30 to 40 percent dystopian. So one of our provocations is what if we reach peak oil in 20 years, that will accelerate solar power.

And there is the chance to educate and influence with the layout of how we sell the food. I want to assume that commercial success and being good to the environment are not mutually exclusive. Maybe they are now because we’re in that early video game phase.

EM: Do you think it will frighten them, as their industry is already beleaguered and being disrupted by new gen companies like Farmigo, AmazonFresh and others.

ML: Phase two is finding partners to build this store with. Half the store will be devoted to private-label products. The other half shelf space for food manufacturers of the world.

We don’t mean it to be frightening. We mean it to be empowering. We’re building the platform where it’s free to dream. You can go to Fancy Food show or Expo West to see what’s happening now. But there’s nowhere to go to see the future of food.

EM: So, what’s next?

ML: In early 2015, we will start building the physical space and the products. We will make 1,000 units of products. They will be priced so people can come and eat them. It’s our goal to make this feel familiar but very different. We will be walking the line. This cannot look like a cliché of the future. When you hear “future market,” you expect this sleek minimal thing. I want to surprise people with a vision of the future. It could have a lot of wood in it, it could have plants in it. It’s not just all touch screens. I want to play off the Soylent ideas of today. Some people say that it’s all pills. But I think the future becomes more organic and farms get closer. The rooftop farm in Gowanus is 1,000 times cheaper, 1,000 times more efficient. I think there’s room for both visions of the future.