Yang Huang spends 12 to 14 hours a day, five or six days a week in the kitchen of Buddakan, the soaring Meatpacking District showplace that turns out, on average, 750 covers of knockout modern Chinese cuisine a night. It’s Huang’s job to oversee a kitchen staff of over 80 and ensure that every plate that exits the wok—including the restaurant’s signature edamame dumplings, redolent of shallots and Sauternes—shimmers with the same perfectly balanced flavors as the last. In pursuit of perfection, he and co-executive chef Brian Ray taste and correct dishes all evening long. By 1:00 or 2:00 in the morning, when they close the kitchen, their legs ache and their palates are spent.

This nightly power graze could dampen the appetite of even the most ardent devotee of Chinese cuisine, but on his day of rest, Huang, who was born in Guangdong, China, refuels with the foods of his homeland. About once a month he leads his staff on a tasting tour of Manhattan’s Chinatown to explain the lesser-known flavors of his native country and open his charges’ minds to new menu ideas.

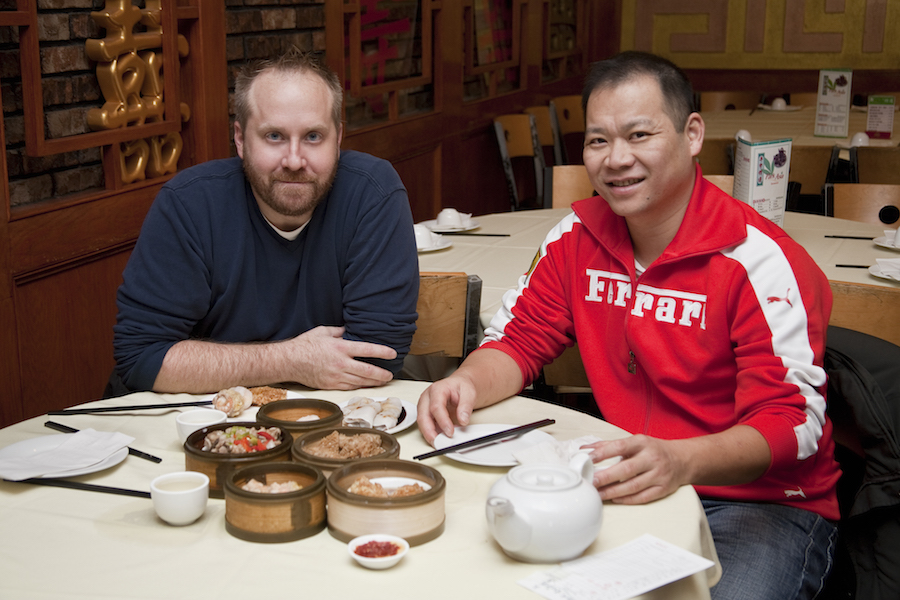

But Huang, whose family moved to Park Slope when he was 12 and who now lives in Sheepshead Bay, is equally at home in Brooklyn’s own bustling Chinatown, the section of Sunset Park known as Little Hong Kong. On a recent chilly morning, I met Huang and Ray there for a taste of the tours on which he leads his cooks and an insider’s guide to the stretch of Eighth Avenue that runs from about 46th to 65th Streets but feels like the other side of the globe.

We’d planned to taste on the go but Huang takes the few drops of rain as a commandment to first sit down for dim sum in a former diner at Park Asia. Cart-pushing ladies jovially greet Yang, who’s clearly a regular, and sling saucy, indecipherable remarks at Ray, who seems accustomed to the treatment. “I’m the token white guy here,” he says good-naturedly.

Chrysanthemum tea appears, and then a parade of dim sum. With Huang ordering, it’s not all your usual fare. Chiu Chao-style dumplings are studded with peanuts, pork and jicama. A dish of pillow-soft, super-light chow fun is delicately sauced and flecked with fragrant cilantro. (These, Yang tells us, are his girlfriend Christy’s favorites.) A plate of pumpkin-filled dumplings arrives, along with bottles of Tsingtao beer. Never mind that it’s before noon; on chef ’s day off he can do as he pleases. Yang, as it happens, never eats before 3:00 p.m. (an adaptation to his work hours), but sipping beer is another matter.

The shrimp and chive “cakes” that arrive next (actually round pan-fried dumplings), are so good that the multitasking challenge of tasting, talking, taking notes and tippling Tsingtao momentarily overwhelms me, but I manage to pull it together in time to focus on the more familiar shrimp har gow, lotus leaf-wrapped sticky rice, tender braised short ribs and taro root dumplings with a shiitake and pork filling.

The skies clear and we head outside. We’ve hardly gone a few steps when Ray’s attention is riveted by whole pigs hanging in the window of a restaurant called Bamboo Garden. Specifically, it’s the crackly-crunchy skin that has Ray agape. “How did they do that?” he asks.

This kind of culinary question is precisely why Huang holds these tours, and he happily describes the two-day technique in detail. After stretching and curing the pig in salt, he explains, flavor is applied in the form of soybean paste and hoisin sauce. After roasting, resting, and inserting a needle to let steam escape, comes more roasting; in the end the crispy brown skin looks like cracked porcelain. “The bigger the pig the better,” says Huang, “because it has thicker skin.” Ray ducks inside and emerges with a smile pasted on his face and a container of sliced roast pork.

We’ve just eaten, though, and there’s shopping to be done. First stop is Fei Long Market, which Huang describes as the “Pathmark of Chinatown.” He’s not kidding. It’s a block long, fluorescent-lit, with produce, meat, fish, frozen and dry goods departments, but the similarity to a standard supermarket ends there. First, the giant produce section stocks exotic specimens: bright-purple dragon fruit, spiky rambutan, Taiwanese guava, and mountain yams that, when grated, turn viscous and delicious. Second, everything is big and cheap, as if Costco went into farming and started growing vegetables of valu-pak dimensions. There are pomelos bigger than a toddler’s head, three-foot-long winter melons, humongous green papayas, “elephant” plums and gorgeous Napa cabbages the size of a toaster oven. (Ray swoons over these. “We’re paying $40 a crate because of the shortage in South Korea,” he yelps. “They’re 39 cents a pound here!”)

Each time we pause to peer, goggle-eyed, at an otherworldly animal, vegetable or mineral, Huang can offer amusing trivia, exactly how to pick the best specimen and ways to cook it. Take cabbages: The unfamiliar flat variety is called “pillow cabbage” in Chinese, while its curly Napa cousin goes by “brain cabbage.” His favorite way to cook kabocha pumpkins is to slice and peel them, then stir-fry the deep orange flesh with Chinese bacon and celery. Of the two kinds of spinach for sale, water and sand spinach, Huang tells me that the variety grown in water is more tender. Goji berry leaves can be bitter, he says, but are good cooked with salty pork. When we arrive at the winter melon bin, he brags, “Mine are bigger,” and whips out his BlackBerry to show a picture of the impressive melon patch he grew behind his home in Sheepshead Bay. The gourds will keep six months in a basement, he says, and are wonderful in soup.

We become so giddy at the size and splendor of Fei Long’s offerings that we forget ourselves. Huang catches Ray, who has been tasting his way through the produce section, munching on some yam leaves and shouts, “Don’t do that, man!” But even the wise guide himself nearly loses his composure at the sight of an oversize bunch of chrysanthemum leaves. “I love these,” Huang exclaims.

Our lesson continues at the meat counter, where Huang points out pig kidney, liver and heart; frozen rabbit and goose; and spareribs cut into chains of about one-inch lengths. “They’re already cut thin, so you take them home, separate them, then steam them with long pepper and black beans, a little sugar, and finger chilies,” Huang says. As we pass the pig uteri, Ray confides, “I’ve never been that hungry.”

At the live fish tank Huang locks onto a glistening, bright-red cut of carp, explaining that the belly is the best part. “I steam it first, and serve it with garlic, ginger and bean paste.” Pompano, he notes, is sometimes called “sea floor chicken.” There are live razor clams, turtles and geoduck clams, freshwater eel, a prehistoric-looking creature known as “pissing shrimp,” and dragon fish, which Huang says have the texture of tofu when cooked. Peering into a giant tub of huge, live frogs, Huang says excitedly, “if I caught a frog that big when I was a kid in China, I wouldn’t have been able to sleep for days, I would have been so happy.”

On our way out he purchases a live black bass—which he likes to cook two ways, using the bones for a soup with mustard greens, and the meat sliced and lightly stir-fried with garlic chive blossoms and salty egg yolk—and some live shrimp. The orange plastic bag writhes.

Next stop is Ten Ren Tea (5817 Eighth Avenue) where Huang likes to buy Wisconsin-cultivated ginseng root (reputed to be better than its Chinese counterpart) for a soup with silky black chicken, Chinese herbs and wolfberries. “This is our Jewish chicken soup,” says Huang. “It restores energy.”

As we examine a sumptuously packaged $300 jar of fermented Puerh “old tea” the black bass Huang is carrying begins to buck like a wild stallion, making a racket in its bag. We repair to the busy street where we can blend in with the crowd.

The avenue is crowded and cacophonous: hawkers display buckets of live blue crab, some on skewers; a vendor boils peanuts in a giant rice cooker. At a window that displays hanging chickens wrapped in white paper bags, Huang explains the birds are stuffed with ginger then roasted, covered in scallions. The sea bass kicks up another wild fuss. Ray coos over live abalone for $6 each. Huang counters, “They were only $3 apiece in Philly!”

As we amble he points out eateries he frequents, including Everett 858 Inc. (5721 Eighth Avenue) a favorite haunt for reasonably priced and delicious fried duck tongue and giant rock crab preparations, and City Café where his favorite dish is braised tofu topped with salty fish.

At PCR Hair Salon (5908 Seventh Avenue), Huang regularly indulges in reflexology treatments ($25 per hour) to soothe his aching feet. Long restaurant hours have taken their toll; Huang’s veins bulge and Ray contends with bone spurs in his heels and plantar fasciitis. The PCR treatment includes a hot water soak with Chinese herbs, which Huang says, “is good for circulation and will take some fungus out, too.” (Ray is partial to full-body acupressure treatments at Health Trail in Manhattan’s Chinatown–only $40 an hour).

Happily for any aching feet, it’s only a short walk to our final destination, Rich Village Restaurant (6009 Seventh Avenue), owned by Huang’s longtime friend Chou Lee. Huang disappears into the kitchen to drop off his wriggling bag, which the chef will prepare for us. Rong Lee, a Buddakan wok cook and Chou Lee’s brother-in-law, sits down at our table but soon disappears into the kitchen. “He’d rather do the cooking himself,” explains Huang.

Our dim sum feast still fills our bellies, but no one can turn down a fresh Cantonese seafood lunch. The shrimp, alive just minutes ago, emerge first, wok-fried and lightly salted. Next come glass noodles with scallion, dried shrimp and Chinese bacon, and Huang cajoles Ray into putting out the crispy-skinned pork he bought at Bamboo Garden. Our sea bass follows, less rambunctious after a bath in bubbling oil and a shower of soy sauce and shredded scallions. A plate of stir-fried amaranth leaves and shiitake gilds the lotus blossom.

Somewhere along the way, a six-pack of Coronas and two Asian pears have materialized at Huang’s side, along with Brian McGovern, the lobster man who supplies both Rich Village and Buddakan.

Bling-laden Meatpacking District and scruffy Sunset Park, diametric opposites, are united at this Brooklyn table, through shared ingredients, inspiration, suppliers and cooks. We toast to a satisfying day at the markets and dig in.

To learn where Huang buys Chinese New Year specialties—like moon cakes, winter melon and a roasted pig—visit ediblebrooklyn.com.